This work was done with Simon, Pav, and Faisal at the Neo Hackathon.

We went into the hackathon with no intention of building something useful. We just wanted a technically clean thing that’s kind of pointless, and to see how far we could push a ridiculous constraint. We chose distributed training for this adventure, with the constraint being to communicate over a completely stupid, nonsensical medium.

We initially considered familiar channels such as Slack, IRC, Zoom, or Discord. But they’d box us into someone else’s interface and protocol, and we would have a hard time dealing with rate limits. After a few long walks around the Ferry Building, we finally found the right kind of ridiculous: webcams.

More concretely, we would set up a bunch of laptops so that every webcam could see every screen. Each laptop would display the data it wanted to send, and all the others would read it through their webcams, decode it, and use it to exchange training updates for distributed training (i.e., no WiFi, no Bluetooth, no wires).

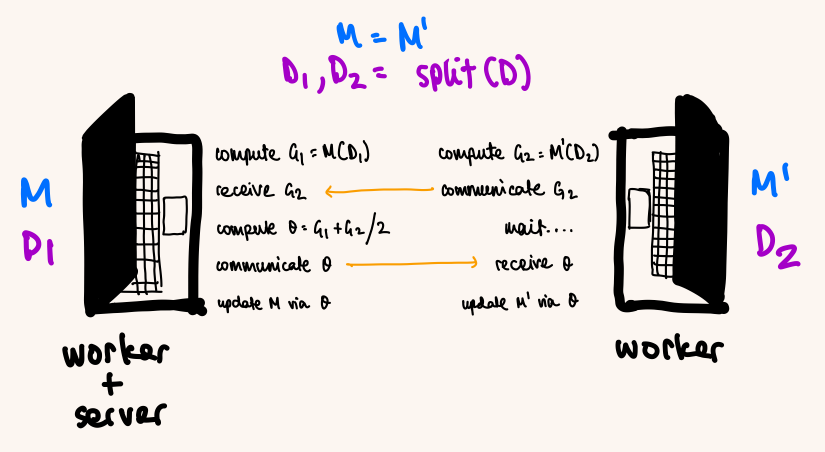

Naturally, we trivialized all aspects of this from the start, as we expected our communication method to be finicky. The smallest “real” distributed setup we could get away with was data parallelism on just two laptops via a synchronous parameter server1. We picked the MNIST dataset to train a small CNN on.

We wanted the demo to be ~4 minutes and the model to reach “good enough” accuracy (>90%) within that window. This meant that if one training step takes seconds, then we can afford about steps end-to-end.

In janky hackathon fashion, we set seconds per step and designed the whole loop around it: ~0.5s for the backward pass, ~3s to send gradients to the worker-server, ~0.5s to average, ~3s to send the averaged gradients back, and ~1s to apply the update on both replicas. That gives ~30 steps for our four-minute demo.

To avoid spending half the demo coordinating, we synchronized clocks once at the start and then ran a fixed send/receive schedule off the clock. It’s hacky, but it meant both machines stayed in lockstep without extra handshakes.

Once that schedule was fixed, everything reduced to one question: how many bits can we push through the webcam link reliably? We had two knobs:

- Push more bits per second through the camera (encoding/decoding + calibration + timing)

- Push fewer bits per step (smaller model, fewer parameters, compression)

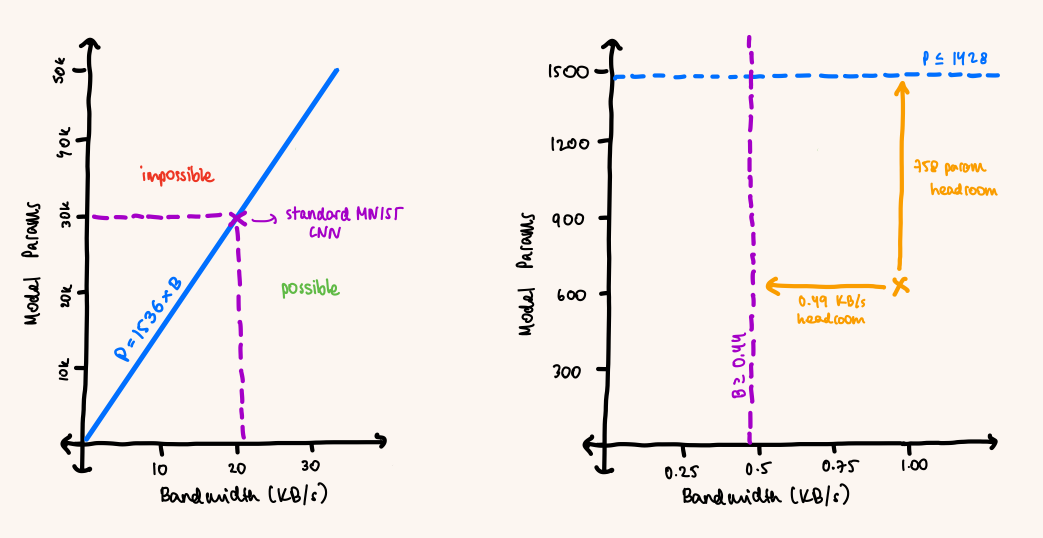

We had a hard budget of 3 seconds to transmit our parameter vector. If we achieve a bandwidth of KB/s, and our model has parameters in bfloat16 (2 bytes each), then the transmission time is:

Setting seconds, we can afford a model of size:

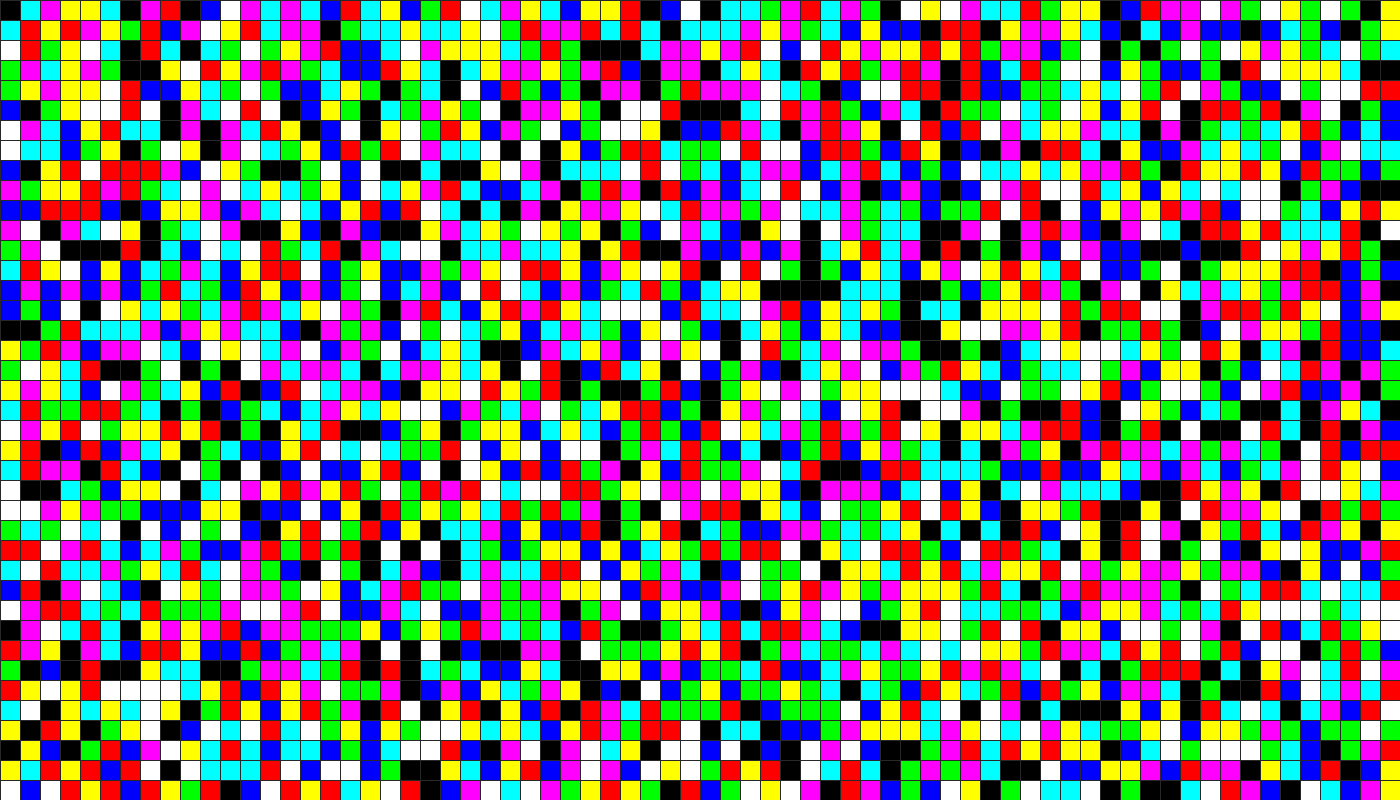

We eventually reached KB/s after a lot of blood, sweat, and tears. Each frame was a 40×70 grid (2800 cells), and we held a frame for a generous ~1 second so the webcam surely wouldn’t drop or misread it.

A sample transmission grid (this can represent a 21x21 bfloat16 tensor :o)

If each cell can take distinguishable colors, it carries bits, so a bfloat16 requires

cells. We found to be the sweet spot: high throughput without decode errors exploding. That made each bfloat16 take cells, so we could represent values per frame.

Calibration for this setup was a nightmare as well. Reflections and shifting room light would nudge the “same” color into a different bucket, and auto-exposure dragged our thresholds over time. At one point, we gave up and started using chairs to shield light between laptops just to keep the colors stable:

It didn't help that we ran into some strange webcam asymmetry issues, too -- one direction would work perfectly while the other randomly dropped frames. The screen refresh rate would sometimes clash with the camera shutter, creating flicker that ruined frames. Most of this work was pretty unglamorous. We spent a lot of time on trial and error: picking colors that actually looked different to the camera, tweaking tolerance settings for each device, and slowing things down so a random misread wouldn't blow up our loss.

Here's what a "reliable" one-way link looked like:

Overall, with KB/s, we could afford a model of

From the other direction, if we have a model with parameters in bfloat16, the minimum bandwidth needed to transmit it in 3 seconds is:

A standard MNIST CNN has tens of thousands of parameters, which would require ~20–30 KB/s (completely infeasible for our webcam link). We didn’t need perfect accuracy, so we aggressively shrunk channels, layers, and fully connected dimensions until the model fit the budget.

What we ended up with is almost comically small, but it got us upto ~92% test accuracy after 30 steps: two convs with a single channel (10 params each) and one tiny fully connected layer (650 params), for 670 total.

With , we needed a minimum bandwidth of

Our achieved bandwidth sets an upper bound on parameters, and our tiny model sets a lower bound on required bandwidth. We barely squeezed into the overlap:

The constraints we just derived, and where our final setup landed (yellow cross on the right)

About 30 minutes before the submission deadline, something finally came together:

We also hooked the model up to an eval pipeline and a webpage, so we could watch it improve live on a third laptop (as narrated beautifully by Simon):

All things considered, this was one of the most fun hackathon projects I’ve done. If you’re choosing what to build, I’d genuinely recommend this vibe.

We’re open to acquisition offers for this breakthrough webcam-based distributed training platform. I’m slightly lazy to make a polished demo video that walks through the full training run end-to-end2, but if you’re interested, the messy repo is here!

- Our setup differs from a traditional parameter servers. One machine served both as the server and worker, while the other just as a worker. Additionally, we are communicating averaged gradients to each machine for local updates, rather than centralizing updates on the server and communicating those updated parameters (a decision made on no sleep). ↩

- There's a video demo on our submission which might shed more light on this. ↩